The world has changed a lot in the last five years, with the effects of the global economic crisis of 2007-8 continuing to be felt by individuals, businesses, governments and international organizations. Universities have of course also been greatly affected – but what have been the biggest changes in the world of international higher education since the crisis hit?

Martin Ince, convener of the QS Global Academic Advisory Board, highlights five key trends in international higher education over the past five years.

1. The continued increase in international student mobility

One surprise, perhaps, is that international student mobility has continued to grow, despite the international economic downturn experienced during this period. In 2009 there were just over 3.7 million students studying outside their home country, according to the OECD publication Education at a Glance. In 2011, the latest year for which we have the numbers, the total was 4.3 million. Of these, 53% of internationally mobile students were from Asia, mainly India, China and Korea.

2. The rise of science and technology-focused universities

2. The rise of science and technology-focused universities

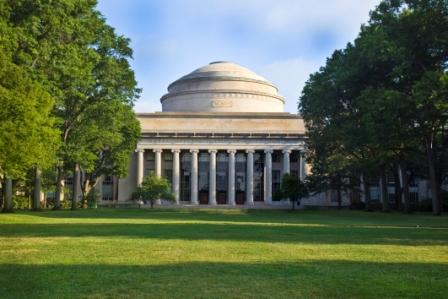

Comparing the QS World University Rankings® for 2008/09 and 2013/14, one of the most obvious changes is MIT’s climb from ninth place to number one. But this is only part of the story. MIT is just one among a number of universities focusing on science and technology subjects which have strengthened their rankings performance over this period.

Other notable examples include the two Swiss Federal Institutes of Technology, ETH Zurich and EPFL, which are both now ranked within the world’s top 20. Meanwhile the UK’s Imperial College London and the US’s California Institute of Technology (Caltech) now stand in 5th and joint 10th position.

3. Changing education hierarchy in Asia

3. Changing education hierarchy in Asia

The past five years also show significant changes to the education hierarchy in Asia, where many countries have been investing heavily in developing and internationalizing their higher education systems. One success story comes from South Korea, which now has six universities ranked in the world’s top 200 – up from three in 2008. The highest ranked of these, Seoul National University (SNU), has climbed from 50th to 35th during this period.

Elsewhere in Asia, progress has not been so clear. In 2008, China had six top-200 universities and its leading institution, Peking University, was tied with SNU in 50th place. This year China has one more entry in the top 200, but Peking is only four places higher than five years ago.

In India the picture is even less promising. India’s top two entries, the Indian Institutes of Technology in Delhi and Bombay, were ranked 154th and 175th in 2008 – and have now fallen to 222 and 233. India’s top general university, Delhi University, has fallen to 441-450, from 274 in 2008.

Japan has also lost ground. In 2008 there were 10 Japanese universities in the top 200. In 2013 there are nine, with the country’s leading institution, Tokyo University, falling from 19th to 32nd place. Having been Asia’s top university five years ago, Tokyo is now behind the top universities in Singapore and Hong Kong – the National University of Singapore is ranked 24th and University of Hong Kong 26th.

4. Overall stability for Continental European universities

4. Overall stability for Continental European universities

While much is changing in Asia, the picture for Continental European universities over the past five years is generally one of remarkable stability.

Mainland European universities tend to fare badly by comparison with their UK counterparts, despite being in a rich, stable part of the world with a massive cultural and scientific heritage and with strong school systems.

But we are seeing some signs of change. The top Continental European university, ETH Zurich, is now 12th in the world, compared to 24th in 2008. This makes it the highest-ranked university not working mainly in English. Its francophone sister institution, EPFL, climbed to 19th this year.

The education systems of European countries like Belgium, the Netherlands and Sweden continue to feature strongly in the middle tiers of the rankings. More surprising is that France had only four top-200 universities in 2008 and has only one more now. Although the École Normale Supérieure was in 28th place in both years, it has little elite company. Germany has a stronger overall top-200 presence, with 13 universities currently ranked at this level.

5. Better visibility for universities worldwide

A final change over the past five years is that far more universities, in a greater range of countries, are attaining international visibility. In part, this is due to the enlarged scope of international higher education rankings such as the QS World University Rankings, which has been gradually expanded to now include 800 universities – compared to 200 in 2008.

This means, for example, that we are now able to see excellent universities in Indonesia, the world’s fourth most populous nation. There are eight in this year’s far deeper rankings, compared to none in the more limited 2008 version. The same applies to Russia – which had only one ranked institution in 2008, and now has 18 in the top 800 – and likewise to other countries in Eastern Europe.

In Latin America, only three universities made the top 200 in 2008, but today’s more extensive rankings show world-class universities across the region. These are led by Sao Paulo in Brazil at 127, up from 196 five years ago.

While South Africa and Egypt remain the only African countries to make a significant impact on the rankings, Middle Eastern countries have gained much greater visibility in the international higher education world. Israel is still the only Middle Eastern country represented in the top 200, but Saudi Arabia, Lebanon and the United Arab Emirates all have universities well within the top 500 – and many with resources that promise continued expansion in the next few years.

This article is adapted from an original written for the QS World University Rankings® 2013/2014 Supplement.